by Charles Alton Wayn

Morrowind Edition

The Complete Blacksmith: Weaponsmithing

The Armorer’s Handbook: Volume I: Light Armor

The Armorer’s Handbook: Volume II: Medium Armor

The Armorer’s Handbook: Volume III: Heavy Armor

Weaponsmithing

In this complete guide to weaponry and repair, weapons will be discussed by material rather than type, as it is important to familiarize yourself with each material technique. With this foundation, even a novice can complete basic field repairs, and it is a handy reference to any blacksmith working with unfamiliar materials. Of course, each weapon type has its nuances. You cannot learn how to balance a weapon from a book; that kind of teaching is better left to the tutelage of a master.

Iron

Working with iron is simple, and the materials are inexpensive. As such, these weapons are fairly common. However, because iron is so malleable, it regularly buckles and loses its edge. It is easily broken and cleaved by weapons made of stronger materials.

Iron clubs, axes, and war hammers are reliable and their construction is simple. Nordic battle axes are also constructed from iron. These weapons are cast, and their heads mounted on iron shafts, which are riveted or bound with leather and resin. A hand-held sharpening stone can put the edge back on an iron axe head, so they can be easily repaired in the field.

Iron blades are forged and hammered into shape, then sharpened. These blades can break and lose their edge, but they are easily repaired. They must also be oiled frequently to prevent rusting. Iron broadswords are effective weapons; longer, thinner blades such as longswords and claymores are more prone to fail in heavy battle. As such, they are primarily used as inexpensive training weapons.

Steel

Steel is one of the most reliable materials for weapon construction. Properly tempered, steel is both strong and flexible, making it the perfect choice for long blades. This common material is also easily obtained and repaired in the field. Steel weapons are preferred in military use, as they are inexpensive and reliable.

Western blade forging employs different techniques than Akavirian forging.

The western technique begins with wrought iron rods, which are fired in a hot forge in a case with powdered carbon for up to four hours. The bars are then twisted together with tongs to form the core of the blade including the tang, which will form the core of the handle. The twisted rods are placed back in the forge and heated until red. A flux is then applied to help weld the metal. This is fired to white heat and hammer welded along the full length of the rods until flattened and completely welded. It must be fired to white heat, as it cools to red several times before the process is complete. It is then allowed to cool slightly, then placed back into the fire while the billet is prepared.

Two steel billets are cut to the desired length of the blade. These are heated to white hot and folded in half into a tight V shape lengthwise. The billets are then fit along the length of each side of the hot iron rod to form the edges of the sword. The steel billets are hammer welded to the iron core. It is then cooled to red hot and flux is applied before re-firing. The sword is repeatedly fired to white heat, and hammer welded along the entire length of the blade. Once it is completely welded, the point is formed. The tang is then cut, and the fuller is shaped, which is the long trench along the center of the blade.

At this point the sword is allowed to cool before the blade is filed, ground, and polished. The blade is then fired again to temper the steel. The steel is heated to a faint red and quenched several times in rapid succession. This will strengthen the blade so it will keep its sharp edge.

An iron bar is hammer welded to the tang just above the blade to create the cross guard. A wooden or iron grip is then cut to size and bored, which is then affixed to the tang using hot resin. The pommel is then constructed from soft metal, which is threaded onto the end of the tang. For sabers, the guard and pommel are constructed separately before being affixed to the tang.

Nordic steel blades are highly ornate. A light acid is applied to the blade in a decorative pattern to etch the blade as the final step of the sword making process.

Akavirian techniques are quite different, and create blades of superior strength and flexibility. This technique is employed to create katanas, tantos, and wakizashis, as well as finer daggers.

The Akavirian technique employs two types of steel, each of varying carbon content. This steel is made by heating iron in a forge with a carbon casing while continuously using air bellows to precisely control the temperature. A softer low carbon steel is made first, and heated in the forge until yellow hot. This is hammered until elongated and folded over several times. Once the steel has been folded and welded ten times over, it is hammered into a long thin metal wedge. This forms the core of the sword, and is set aside as the jacket steel is prepared.

The jacket steel is a harder steel with a higher carbon content. It is hammered out until it is slightly longer than the core steel. This is then reheated and wrapped around the hot core. These are then heated and hammer welded together in a similar manner to the western method above. After the two pieces of steel are completely joined with no seams, it is hammered to the desired length and a slight curvature is added to the blade.

At this point the blade is ground and shaped. The edge is not sharpened, nor is the blade polished at this time. A course stone is rubbed along the blade to provide adhesion for the clay that is applied during the heat treating process.

Heat treating the blade requires it to be first coated with a clay mixture. This controls the temperature and relative cooling of the blade, in much the same way as oil quenching, which is done to gradually cool the metal, and used to create the steel tools employed by smiths. A thick layer of clay is applied along the top and upper sides of the blade, and a much thinner layer along the edge. This is applied in a pattern which will be visible and add to the sword’s beauty and worth. The blade is then set aside and the clay allowed to dry for about an hour.

The blade is then heated in the forge, slowly pulled back and forth through the hot coals until it has been uniformly heated bright red-orange. This is typically done at night, so the color of the heat can be accurately observed. Once the blade attains the desired heat, it is plunged into cold water. The blade must then be tempered by heating it to a faint red and re-quenching again to relieve the stresses that have built up in the blade.

At this point the clay is removed and the curvature of the blade is refined by careful hammering. The blade must then be polished, which is a careful and expert process. It is first rough polished with a metal file in a decorative pattern, and then turned over to the master polisher. First a foundation polish is applied using heavy grit polishing stones. An intermediate polish is then applied using a medium grit stone, and then the finish polish is done with a special paste applied to fine grit stones.

Heavier steel weapons are simply cast rather than hammer formed. Axe heads are cast into a basic form, often with a decorative mold, and then the edge of the blade is hammered thin before sharpening and polishing. Steel longbows, on the other hand, are hammer formed in a method similar to the western swordmaking process.

Silver

Silver weapons are primarily used against magical creatures, which are immune to physical damage by ordinary weapons. Silver is a soft ductile metal, and as such loses its edge fairly quickly, but its unique properties make it invaluable.

Silver weapons are often cast over a solid iron core to strengthen the weapon. Silver staffs and blade handles are ornate, while the blades themselves are quite plain, as they are hammer welded over an iron core. They must be sharpened frequently, and are easily beaten back into shape. The silver staff is one of the more effective weapons, as it is solid, and often fortified with enchantments.

Chitin and Bonemold

Chitin and Bonemold are both laminates, which are most effectively employed in the construction of bows and arrows. Chitin shortbows are fairly weak, but bonemold longbows are among the best. Dreugh shell is another laminate used to create weapons such as clubs and staffs.

You would be correct in thinking chitin not a good material to create daggers, clubs, spears, and war axes, but they do exist. They are some of the least effective weapons you can find. They are often spiked or serrated to increase the damage they are capable of dealing, but this material is too lightweight and flimsy to do any real damage in battle. They also require frequent repair, which is at least simple and utilizes local materials. Chitin weapons are a holdover from early nomadic Ashlanders, who didn’t have ready access to imported iron.

Repairing laminate weapons is a fairly simple process involving the heavy application of resins. When pieces of the weapon begin to flake away, they can be bound with heavy twine or leather while the resin sets. Severe breakage requires some replacement material to strengthen the compromised area.

For creating a laminate bow, we will use bonemold as an example. All laminate bows are constructed using a bow form. Today the Dunmer use a wrought iron form clamped onto a wooden backing, but they can be made from any strong material. The iron is hammered to match the exact length and curvature of the bow, then mounted onto the wooden back with pins.

Next, the bone is prepared. These bone slats must match the length of the finished bow. They are cut thin, and tapered, with the thickest part in the center. Thicker, shorter, carved bones are used to build up the center hand grip. These sheets of bone are boiled to remove any residue. They are then stretched over the form, and a hot resin is applied to each layer on each side. The bow is slowly built up from thin slats, and tightly clamped to the form. Once the bow complete, it is then treated with steam for several hours before it is allowed to cool. The clamps are adjusted every hour during the steaming process so the bow gradually fits more tightly over the form. The bow is then set aside, still firmly clamped to the form, for two days to allow the resin to completely set.

Once the bow has set, it is broken away from the bow form and filed and sanded. This is done to place the nocks in the bow and correct any errors in the bow’s balance. Once the bow is the correct shape, it is completely coated in a thin resin to waterproof it, and allowed dry for several hours before it is strung for the first time.

Bonemold and chitin arrows are constructed out of single long pieces of carved material, and are not laminated. The heads are mounted and secured with a thick resin. These arrows are often fletched with the same materials, which is bone and chitin respectively, as opposed to using feather.

Glass

Glass is used to create some of the sharpest blades known in the world. It can hold a sharper edge than any known material, and is incredibly lightweight. It also distributes shock well and is fairly flexible. This means it can be cut into long fine blades that are incredibly sturdy. This incredible material is native to Morrowind, and glass weapons have been created by the finest elven craftsmen for centuries.

These blades are cut from solid pieces of glass. The craftsman must carefully study the grain of the crystal structure before attempting to shape the stone by knapping. This is the process of gradually chipping away at the stone to create a razor thin edge. Fine chisels are used in this process, and elven craftsmen are able to cut the stone so fine that no traces of this process can be seen.

Once the blade is cut, be it a long blade or an axe head, the stone is mounted in a soft yet durable alloy. This is affixed in place with a combination of resins, and hammered and burnished settings. This metal is also inlaid with smaller pieces of glass to create intricate designs. Axe heads and staffs are mounted with glass spikes, which are equally deadly.

Glass is also used to create arrows and light throwing weapons. Glass can be carved into incredibly thin shafts, which are light, strong, and flexible, making them perfectly balanced projectiles.

Ebony

Raw ebony is an incredibly heavy material, but a perfectly balanced ebony weapon is one of the most effective and deadly. They are also beautifully crafted and ornate, often decorated in gold, exhibiting the height of elven craftsmanship. Ebony weapons are entirely crafted out of this material, as opposed to glass, which is mounted in metal. This stone can be used to create heavy blunt weapons or finely sharpened blades. These weapons are rare and well worth their weight in gold.

Unlike glass, ebony is worked hot. When this stone is heated, it becomes somewhat ductile, allowing a smith to form it with hammers. For the most part, ebony is carved into shape, since it cannot bend far. The stone is heated until it begins to glow a dull red, then hammered with a hot chisel. The stone becomes almost soft, allowing incredibly smooth cuts. Working with this stone cold results in tiny fractures that compromise the strength of the material, eventually leading to breakage.

Once the weapon is carved, it is heated again, which results in a gleaming polish. At this point the gold leaf is applied while the stone is still warm, requiring no resins to set it in place. The weapon is then allowed to air cool. Hot ebony must never be quenched, because the shock would cause the stone to shatter.

Deadric

Deadric weapons are also made of ebony, but they are infused with the souls of lesser deadra. These are entirely constructed by deadra in Oblivion. As such, these weapons are incredibly rare in our world. deadric weapons can be temporarily summoned and bound to the caster using conjuration spells. These weapons return to Oblivion the moment the spell wears off.

These weapons cannot be made by mortal kind, but they can be repaired. Repairs must be done at night, as this is the time when the shroud of Oblivion is not obscured. They must also be repaired with the same care and considerations as other ebony weapons.

Dwemer

The dwemer were expert metallurgists and master craftsmen. Their weapons, though heavy, are perfectly balanced. These are created out of alloys, the secrets of which have been lost to time. Unfortunately, the ban on trade in dwemer artifacts means few blacksmiths have had the opportunity to study these weapons, so not much is known about them.

The Armorer’s Handbook: Volume I: Light Armor

This volume of the Armorer’s Handbook covers the various types of light armor found in Morrowind. This handy reference will familiarize you with the construction of armor unique to this province, as well as some old familiar techniques. Of course, the best way to learn how to create these special types of armor is to travel and seek the guidance of masters. This guide will provide you with the basic knowledge you’ll need not to look like a fool when you attempt to repair unfamiliar armors, but really the best way of learning is by doing.

Nordic Fur

Nords are best known for creating light leather armor out of the hides of animals native to Skyrim and Solstheim, such as the bear and wolf. This armor provides comfort and warmth, and is light and flexible. However, it does not offer great protection in battle. It can be pierced easily by bladed weapons, and offers little protection from blunt trauma. This armor is best employed by hunters, as it offers the best protection from animal attacks and wayward arrows. Nordic bear armor is a heavier type of fur armor, which often dons the bear’s full head as a helm. It is classified as a medium type armor.

Fur armor is constructed using tanned hides and heavy stitching. The leather is carefully treated so it does not lose its fur. Thick hides are generally preferred. Tannins such as dung or urine are not used in this process. Instead, the process of brain tanning is employed. Oddly enough, each animal has just enough brains to tan its own hide, so tanning is often done in the field soon after skinning. Nords traditionally believe brain tanning infuses the hide with the spirit of the animal.

After the hide is stretched across wooden stakes, it is fleshed using stone or bone tools. All meat and fat must be removed, leaving nothing but clean skin on the flesh side. After this is done, the brains are boiled in water and applied to the entire skin side of the hide. The hide is then left out in the sun for eight hours before submerging in water overnight.

The next morning, the hide is re-staked and allowed to drain before working the hide over with a graining tool: a smooth stick with a round blunted point that fits comfortably in the hand. The hide must be worked until it is completely dry or else it will stiffen. Once the hide is dry, it is carefully worked by rubbing, skin-side down, over a smooth tree branch. The heat and friction will break up the grain further and complete the drying process. These hides can then be form molded by smoke curing, as opposed to boiling, which will prevent it from stiffening again on contact with water. When treating the hides you want them to retain their softness and elasticity.

For heavier leather armor, such as the Nordic leather shield, this is treated with tannins, and boiling and waxing the leather. The leather will become incredibly stiff; it will not be possible to stitch together after this point. Instead, holes must be punched before the final treatment in the tanning process, and the leather is stitched over the shield frame using leather bindings before the final curing.

The warmth this armor provides, as well as its low cost, make it an excellent choice for hunting expeditions in colder regions. It is hardly suitable for most other purposes however. As such, it is hardly a popular choice in Morrowind.

Netch Leather

This armor is unique to the dunmer people. It is made with netch hide, which is native to Vvardenfell. Typically found in the Ascadian Isles, the netch is a large floating creature, held aloft by internal gasses in its body. The hide of the bull netch is sturdy and supple, and makes leather armor of superior quality. The netch is also an incredibly large creature, providing ample skin to work with in a single kill. Netch leather is also thinner and more durable than other leather types.

Netch armor comes in two varieties: in full sets of soft leather armor, and boiled helms and cuirasses. Because the netch has a smooth skin, de-furring the hide is not necessary. After the skin is fleshed with stone or bone tools, it is tanned. First the hide is bated using dung, which is rubbed into the skin. This relaxes the leather and prepares it for tanning. The dung is then washed from the hide and soaked by hanging the hide in a pit filled with water and crushed bark, which is the source of the tannins. The hide is soaked like this for two days before it is spread out to dry.

This tanning process leaves the leather soft and supple. It can be easily stitched and formed before steam curing or boiling. Steam curing allows the leather to retain its softness even after it is formed, and it must be worked with a graining tool during this process. Boiling will create a much harder and sturdier armor, but it loses its flexibility. For this reason, only helms and cuirasses are treated in this manner.

This armor is comfortable and affordable, and utilizes native materials. As such, it is the armor of choice amongst the Ashlanders and other peoples of Morrowind. It does not offer much in the way of protection in battle, but for daily protection it is quite suitable.

Imperial Studded Leather

This armor is imported from the mainland. As such, it is not commonly used in Vvardenfell, save for members of the Imperial Legion. The leather is tanned and cured in much the same way as other leather armors, after which studs are embedded in the leather. The embedded metal studs offer greater protection from bladed weapons, but little protection from blunt weapons. This armor is typically used during training rather than in battle.

Chitin

Chitin is a type of light plate armor native to Vvardenfell, and is commonly favored by nomads and Ashlanders. It is constructed by laminating several layers of insect shell, glued with organic resins. The materials are gathered from the various species of kwama native to Vvardenfell, and other insects such as the shalk are used to provide the resins. Creating chitin armor is a time consuming process, but since it only requires local materials, it is cheap, easily produced, and commonly found in this province.

The armor plates are boiled, then carefully cut. The boiling process softens the plates so they can be worked. The layers are pressed together with wooden blocks after the resin is applied. The layered plates are then stretched, as much as they can be, and tied over a dummy form. The formed plates are steam treated in place to complete the lamination process, then lacquered.

Chitin is also used to create weapons, which are light and flexible. The edges are typically serrated because the blades cannot hold the superior edges of metal or glass. However, they are native and affordable, so they are quite commonly found.

This armor is light and comfortable. Though it lacks the suppleness of leather armors, it is jointed and formed in a way that provides maximum flexibility. It is more resistant to blunt trauma, but can be easily penetrated by heavy bladed weapons. The closed chitin helms provide excellent protection from ash storms, and are therefore worn by many dunmer living in Vvardenfell.

Glass

Glass armor is the paramount of light armor. Its delicate and ornate elven design is unusual, but it happens to be one of the superior armors of the world. It is also the most enchantable of light armors. Glass armor is difficult to make, and expensive. The material costs alone mean only finest Dunmer craftsmen dare touch it. Nevertheless, it is important for any armorer to familiarize himself with the basics of its construction.

The base plates of glass armor are constructed much in the same way as any plate armor. The joints are incredibly tight and precise, allowing for greater ease of movement. The plates are forged out of rare metals and embedded with large glass studs. The metal alone is soft and not suitable for armor; the glass studs provide its true strength. The metal’s softness allows it to be easily carved with graving tools and set with glass stones.

The settings are typically done by cold forming. The designs are embossed by chasing, which is working with a hammer and chisel along the top side of the metal plate. A graver is used to cut the bezel. This seat is cut deep, and perfectly shaped to the stone. Once the stone is fit, a setting punch and hammer is used to carefully form a wall of metal around the stone. The metal is then burnished, which work-hardens the soft metal so it holds the stone firm. Often, a hot resin is lightly applied to the interior of the bezels before setting, which helps keep the stones firmly glued in place.

Heat is not recommended when repairing these armors, nor is it required. The metal is soft enough to work with cold. A small hammer and a light touch is needed. Broken glass stones can be replaced and set with hot resin. Some cutting with graving tools might be required to accommodate the new stone’s shape, and the metal can be pushed back up around it to tighten the fit.

Glass armor is lightweight, highly flexible, and stronger than steel. It is resistant to bladed weapons, and distributes shock well, making it highly resistant to blunt force. It is in fact stronger than most medium armors. The volcanic glass also produces blades of unparalleled sharpness. These weapons are light, flexible, and sturdy, making them much sought after. This armor is favored by the Buoyant Armigers of Vvardenfell, many of whom are nobles of Great House Indoril. Glass creates a light battle armor of the highest quality.

The next volume of The Armorer’s Handbook will cover medium armor, and how to create and repair chain, ring, and scale mail, as well as some types of light plate and heavier laminates.

The Armorer’s Handbook: Volume II: Medium Armor

This volume of the Armorer’s Handbook covers the various types of medium armor found in Morrowind. This handy reference will familiarize you with the construction of armor unique to this province, as well as some old familiar techniques. Of course, the best way to learn how to create these special types of armor is to travel and seek the guidance of masters. This guide will provide you with the basic knowledge you’ll need not to look like a fool when you attempt to repair unfamiliar armors, but really the best way of learning is by doing.

Imperial Chain

Chain mail is one of the most basic types of metal armor, one of the easiest to produce, and also one of the lightest and most flexible. The chain is woven into tunics and reinforced with heavy leather straps, which is worn loose over a heavy shirt. Imperial chain greaves and pauldrons are actually constructed from light plate with chain mail reinforcing the joints.

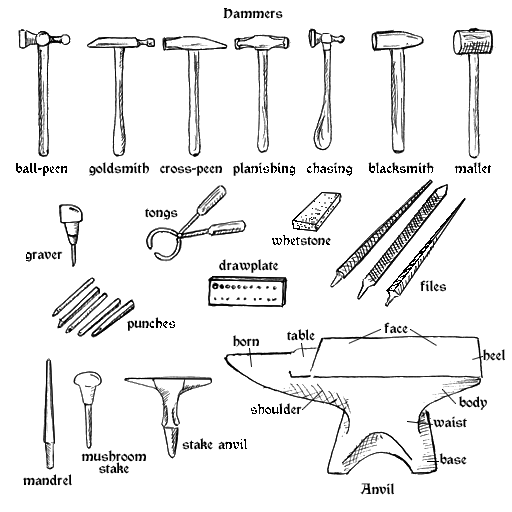

Metal rings are created by drawing wire and hammering it into a coil around a metal or wooden mandrel. Individual rings are then cut from the coil. For iron, which is more commonly used, this process is often done cold. This work-hardens the metal, producing strong rings that are only slightly flexible. For steel rings, the process must be done hot, and it is tempered after the mail is completely woven.

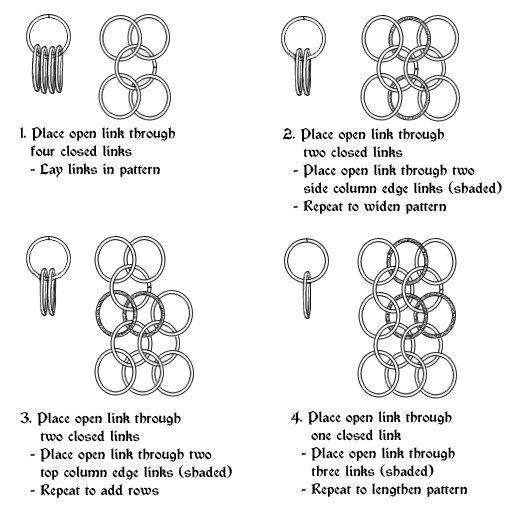

Imperial chain mail uses a basic 1 into 4 pattern. This means every link in the pattern goes into four other links. A diagram is provided at the end of this book to illustrate this simple and effective technique. It creates a strong flexible mail that allows the pattern to expand and contract along the body, but not down the body, all without putting stress on individual links.

Imperial chain armor is primarily used by light infantry, guards, and archers of the Imperial Legion. It is more cost effective, easier to repair in the field, and offers more mobility than plate armor. It is nearly impervious to piercing damage by arrows, and highly resistant to slashing damage. However, it does not provide much protection from extreme blunt force.

Imperial Dragonscale

Imperial dragonscale armor offers nearly double the protection of chain mail, but being more costly to produce, it only used to create helms, cuirasses, and shields. It is the invention of the Tseaci, the Serpent Folk of Akavir. Since it is expensive and difficult to produce, it is uncommon.

The techniques used to create dragonscale armor are long-held secret, but a few conclusions regarding its construction can be made through observation. The scales themselves are tightly riveted onto a foundation – leather for the cuirass, and metal for the helm and shield. They appear to be made from actual scales. Though not likely the scales of real dragons, they are possibly from a large Akivirian serpent creature.

Dragonscale armor is primarily employed by the Imperial Legion, and tends to be a status symbol within their ranks due to its relative expense and rarity.

Nordic Ringmail

Ring armor is closely related to scale or studded leather armor. It is created by sewing metal rings onto a leather or cloth foundation. Unlike chain mail, the rings are not interlocked. Though this armor does not provide as much protection as chain mail, it is not as heavy, and more flexible. Nords are renowned for their leatherwork, which forms the base of their ring mail.

These simple rings are constructed from thick iron wire. The wire is created by hammering small ingots until they are long and thin, which is then drawn through a plate with a set of tongs. The wire is then heated and quenched to return the metal’s ductility so it can be cold formed. Hammering the wire into rings work-hardens the metal, which makes them strong and resistant to further bending. These rings are then sewn onto the leather base armor to create an armor more resistant to piercing and slashing damage.

Of all medium armor classes, ring armor offers the least protection, but is inexpensive to produce. Nordic ringmail armor is typically used by light infantry and archers, as it provides more comfort and mobility in battle.

Bonemold

This type of armor is native to Morrowind, and used extensively by city guards and nobility in native dunmer cities. Each Great House of the dunmer has their own bonemold forms. Bonemold armor, made entirely from bone and resin, has similarities to chitin armor but is stronger and heavier. It is relatively lightweight, but restricts mobility. Training is required to move with ease in this armor, as with any plate armor.

Bonemold is constructed by carving and shaping bones and shells, and gluing them in place with resins. First, the pieces are carved so they fit together seamlessly. A hot resin is applied, and the bonemold plate is pressed together with wooden blocks and allowed to set. Once the resin is set, the entire piece is immersed in hot water, which will soften the resin just enough so the plate can be formed. The warmed bone plate is then tightly strapped to a dummy form and the resin is allowed to set again. A light coating of hot resin is then applied to the entire surface, which waterproofs the plate and hardens the form.

Repairing bonemold armor is not too difficult as it only requires locally found materials. Bonemold does not dent, but does tend to crack. Small cracks can be repaired with a heavy application of resin. Larger cracks require a small wedge of carved bone to fill the damaged area. The bones of any animal can be used, and any resin will do.

Bonemold is also used to create quality bows and arrows. The lightness and flexibility of resin infused bone, as well as the readiness of the materials in a land somewhat sparse with trees, make this the common bow of choice in Vvardenfell. The price of bonemold armor varies greatly according to style, and not all styles are equal in their protection. It is all relatively affordable though, and its protection is decent.

Indoril

Indoril armor is an ornate, medium weight type of chitin armor native to the dunmer. This high quality armor is reserved for Ordinators, the guards of the Tribunal Temple. In fact, it is considered a grave insult to the Ordinators to don their sacred armor. Doing so carries a death penalty in Morrowind, and there is no reprieve.

The Indoril helm is perhaps the most fascinating. Every Ordinator wears the face of Vehk, or Vivec, one of the gods of the Tribunal, as they are considered his personal guard. The mask covers the entire face. It is a detailed laminate constructed from chitin and resin. The cuirass also mimics the body, with a molded chest and spine. This chitinous laminate is molded over a cloth form, which allows for greater ease of movement. It is also heavily decorated in gold leaf.

Her Hand’s armor is a heavy variant of Indoril armor worn by the High Ordinators of Mournhold. It too is sacred to the dunmer, and carries the same death penalty if worn by outsiders. It is a laminate constructed in a similar manner to Indoril armor, but covers more of the body.

Dreugh

This armor is another type of laminate composed entirely from dreugh shells. The dreugh is a dangerous waterborne creature, and its single massive claw is used to make shields. A helm and cuirass are also made from dreugh shell, as well as a couple blunt weapons. The dreugh’s outer shell is thick and sturdy, and it creates a tough armor that doesn’t sacrifice mobility.

Dreugh armor is made in much the same way as other laminates. It can be slightly tougher to repair, as the materials are not as readily found as bone or chitin, but it can be easily patched using other materials.

Orcish

Orcish armor is a light steel plate. It is ornate and based on elven designs. Worn over padded clothing, it offers more comfort and mobility than other steel plate armors. These armors are prized for their craftsmanship, and are fairly expensive to produce. Orcish plate can also hold decent enchantments.

Orcish craftsmen hammer the steel plates into thin sheets, which is then annealed after it is formed. The annealing process heats the metal to a temperature that softens the metal, and is then cooled by quenching in water. The steel is then worked cold with hammers and chisels to create the embossed designs using a technique called repousse. Repousse is working from the back of the metal plate to raise elements along the front. Afterward, the metal is chased, which is embossing from the front of the panel to work detail into the raised elements. The finished plates are then polished, and either linked or riveted in place.

This armor offers excellent protection and mobility. It is relatively lightweight, and favored by both orcs and imperial soldiers. However, it is quite rare and incredibly expensive. Most orcish armor has been passed down family lines for generations, so great care must be taken when repairing this armor. A delicate touch must be used, as the plate is thin and it would be a terrible shame to damage the ornate embossed designs. Small hammers are typically used to repair this type of armor, and minimal heat is applied.

Adamantium

Adamantium is a type of ore unique to the Morrowind mainland. This metal has incredible properties, used to produce a lightweight plate armor that can hold the highest enchantments in the medium armor class. Adamantium can be hammered into paper-thin sheets and still remain stronger than steel. Adamantium ore is incredibly rare, so it, and its armor fetches a high price on the market.

Adamantium is difficult to work with, requiring extreme heat to smelt and create ingots. Also, this metal cannot be brazed or soldered; the metal will not fuse with an alloy of a lower melting point, so soldered joints will simply crack and flake away. Adamantium ingots must be close to the exact mass required to create a single plate. If the amount is short, attempting to fuse the metal will cause the plates to buckle and crack, requiring the smith to start over from scratch. Once the plate is hammered to the right size and thickness, the metal must be heated before it can be cut with a sharp punch.

To hammer adamantium into plates, the metal must be heated until bright yellow hot. Once the plates are thin enough to be formed, they can be worked cold with frequent annealing. The metal is then polished with a planishing hammer. The planishing hammer has two sides: a slightly rounded face on one, and a flat face with rounded edge on the other. The rounded face is used, and must be frequently polished with rouge and a soft cloth. Blows are struck in rapid succession, at a steady rate, evenly across the metal’s surface. This creates an even polish across the plate, which can then be finished with a light application of rouge. Adamantium can be lightly embossed using chasing tools, creating an elegant finished product.

The finished plates are either linked or riveted in place. These rivets, made from adamantium wire, can be incredibly small and made barely visible on the surface. They are often hidden by lightly chased designs along the plates’ edges.

Repairing Adamantium requires high heat and a heavy hammer, and dents can be worked out quite easily. It is difficult to cut through, even with a heavy war axe, being nearly impervious to piercing or slashing damage. However, if it does somehow develop a crack, it can only be patched in the field by riveting a plate over top the damage. A full repair requires the manufacture of a replacement plate. Thankfully, this kind of damage is incredibly rare. Adamantium, unlike iron or steel, does not rust, so oiling this armor is unnecessary.

Another interesting property of adamantium is it changes color when heated. Its surface will transform through the full color spectrum as the temperature rises. This color is removed during the polishing process, but has its uses in blacksmithing. Each color coincides with a specific temperature. This, combined with its incredibly high melting point, means small adamantium plates can be used as temperature gauges in forges.

Ice Armor

Ice armor is created by a rare nordic ore called stalhrim. Stalhrim is a type of glass, similar to ebony, rather than a metal. Used by ancient nords in their burial rituals, it is only found in Skyrim and the island of Solstheim. It is incredibly rare, so armor and weapons made from this material are almost unheard of. Its enchantment value is mid-range, but it offers the highest level of protection in the medium armor class.

Stalhrim is not as supple as ebony when heated. In fact, it seems to defy heat altogether, remaining inert no matter what the temperature. The stone must be cut precisely using chisels. Constructing ice armor is closer to masonry than smithing. Stalhrim ore is also lightweight, so even though it can only be thickly cut, it still creates an armor of medium weight.

Crafting armor from stalhrim requires precise measurements. The cut stone is inlaid over a metal base, using an alloy similar to the metal used to create glass armor. The stalhrim is cut to form from large blocks, then mounted onto the metal base using resin coated pins. Smaller blocks are cut and inlaid into the finer elements using a liberal application of resins. Stalhrim has a natural polish when cut, and so polishing the finished product is not necessary.

Stalhrim is practically impervious to heavy blows, cutting, or piercing damage. Its weak spots lie in the soft base metal it is mounted on. Often the metal base and mounting pins require repair, but repairing the stonework itself is not an issue. You can heat and beat away at the surrounding metal without compromising the strength of the stone.

The next volume of The Armorer’s Handbook will cover heavy armor, and how to create and repair scale, plate, and ebony.

The Armorer’s Handbook: Volume III: Heavy Armor

This volume of the Armorer’s Handbook covers the various types of heavy armor found in Morrowind. This handy reference will familiarize you with the construction of armor unique to this province, as well as some old familiar techniques. Of course, the best way to learn how to create these special types of armor is to travel and seek the guidance of masters. This guide will provide you with the basic knowledge you’ll need not to look like a fool when you attempt to repair unfamiliar armors, but really the best way of learning is by doing.

Iron Plate

Iron is one of the most abundant and inexpensive materials used to create plate armor, but offers the least protection. Iron can be easily cleaved and dented. In fact, many medium armors offer greater protection than heavy iron plate. Nevertheless, its low cost makes it common for front lines troops in battle. Nords have their own style of iron helms and cuirasses, which are heavier and offer slightly better protection.

Forging iron is one of the oldest techniques in the world. The metal offers little resistance when formed into thick plate. In the field, a heavy hammer and low temperature campfire are enough to repair this armor. Iron armor must be oiled frequently to prevent it from rusting.

Steel Plate

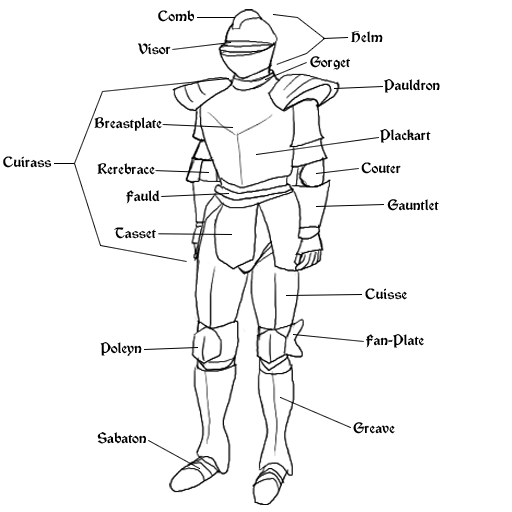

Steel, being a strong alloy of iron, is also fairly common. Unlike iron, steel armor has a prominent fauld to protect the groin area, which offers more comfort and mobility than closely formed, fully closed plate grieves. Steel, stronger than iron, can be hammered into thinner plates, which increases its relative comfort and mobility. Steel also does not rust as quickly as iron.

Imperial steel armor is coated with black oxide to prevent corrosion, and also frequently decorated in gold leaf. The joints are protected with chain mail. The fauld and tassets are constructed from chain mail and studded leather. Imperial steel armor also has an open helm, compared to the full closed helm of regular steel armor.

Steel is smelted by mixing iron with approximately 2% carbon, the most common source being found in charcoal, which can be obtained by burning wood in a closed forge. The steel ingot is then hammered into thin plates. Once the metal is close to the desired thickness, the metal must be frequently annealed: brought up to a dark red hot before quenching in water. This softens the metal enough to work it cold to create the finished form.

Once the plates are fully formed and cut to size, the steel is polished before it is tempered. Tempering steel makes sure it is neither too soft nor brittle. The steel must be heated evenly and observed carefully in this phase. A slow change in surface color will indicate the steel has reached the correct temperature. If working in the dark, a faint red glow will indicate the steel has reached the correct temperature. Otherwise, one must look carefully at the surface changes in the metal. The surface will change from yellow to brown, and eventually become tinted blue. The steel must be removed from heat and immediately quenched once it reaches this point. This process is repeated several times to create an even temper across the whole plate.

Steel armor is the preferred armor for soldiers in the field. It is relatively easy to maintain; only occasional oiling is necessary to prevent rusting, and dents can be easily repaired in the field. Though steel requires a higher temperature than iron to work with, a simple campfire can be brought up to temperature with a few carefully placed bricks and a set of bellows.

Imperial Silver

The Imperial silver helm and cuirass are frequently used in the Imperial Legion and Royal Guard, being finer and more ornate than steel or iron plate. This incredibly thick plate also offers better protection. Real silver is more frequently used in weapons, as most magical creatures are impervious to ordinary weapons, but silver armor is actually a misnomer. This is actually a reference to silver steel, a high carbon steel. It is harder than ordinary steel, and retains a much brighter shine.

Nordic Mail

The nords have some of the finest mail armor in the world. This heavy armor covers the whole body, and is incredibly hard to penetrate. This hybrid armor offers greater mobility than regular plate and, unlike most mail, is resistant to heavy blows. The armor is lined with fine fur, making it comfortable as well. It is however difficult and costly to produce, making it far out of the price range of the average soldier. The most elegant armor the nords have ever created, it rivals some of the best elven craftsmanship.

Nordic mail is a combination of plate, mail, and scale. The helm, pauldrons, boots, and chestpiece are constructed from heavy plate. This plate is embossed in ornate designs, sometimes leafed with gold. The scales of the cuirass are tightly spaced and affixed to a heavy leather foundation. The chain mail covering the rest of the body is also affixed to a leather foundation; however, it is not considered ring armor because the links are interwoven.

Repairing this armor is complicated. Because the entire thing is affixed to a leather foundation, the plate cannot be heated and repaired before removing it. The chain and scale elements are much easier to replace however.

Ebony

Ebony is a rare volcanic glass found primarily near the Red Mountain region in Vvardenfell. It is so named because of its black opaque glassy surface. This armor is highly ornate and often decorated in gold leaf. It offers the best protection of any armor and can hold the highest enchantments, only being surpassed in this respect by daedric armor. Ebony ore is incredibly valuable, so this armor is costly to produce. Its price and rarity means it is typically only affordable to wealthy nobles. It comes as no surprise this armor is worn as a status symbol.

Raw ebony ore is chiseled into thick blocks while cold, then heated to extreme temperatures to carve it into elegant smooth shapes. This glass becomes somewhat ductile when heated, and also acquires a glossy sheen. Therefore, heat is used to polish the final product, and gold leaf is applied with low heat to weld it to the stone. The plates are then affixed to a foundation of cloth or leather using resins.

Repairing ebony requires heating before working it with a hammer, otherwise it will develop small cracks that will compromise the armor’s strength. These cracks can be sealed with resins should they develop. Because ebony is somewhat brittle, it cannot sustain repetitive heavy blows or cleaving. It is however nearly impervious to slashing and piercing damage.

Ebony armor is incredibly heavy, and does not offer much in the way of mobility. Feather enchantments are often applied to reduce its weight, making the wearer more mobile in battle.

Daedric

Daedric armor is made from raw ebony. Forged by the daedra themselves in Oblivion, using the souls of lesser daedra, this deep black armor attains a magical red glow along its edges. This armor is the battle armor of the dremora, and is incredibly rare, as it often finds its home back in Oblivion. Conjurations spells can be used to bind daedric armor to the caster. However, these effects are temporary and, once the spell wears off, the armor vanishes.

This armor is so rare, the price on the open market makes it nearly impossible to buy or sell. It is the strongest armor known in the world, and can also contain the greatest enchantments. As with any armor type, shields are capable of holding the highest enchantments, and daedric armor is no exception. The daedric tower shield is the single most enchantable artifact in the world.

Because of this armor’s daedric nature, it cannot be crafted by mortal kind. It can however be repaired, but great care must be taken. Daedric armor must always be worked on at night, as this is the time when the shroud of Oblivion is not obscured. It must also be worked hot, just as any other ebony armor. Daedric armor is not as prone to cracking under stress as regular ebony armor, so it rarely requires repair.

Dwemer

When the dwemer disappeared, they took their secrets of metallurgy with them, and unfortunately the Imperial trade ban on dwemer artifacts means smiths and armorers have not had much opportunity to study their secrets. This metal is heavier than steel, and highly resistant to corrosion. The dwemer seemed to use the same alloy used to construct their centurions. It is precisely jointed, and gaps are minimized for better protection. Unfortunately, little more is known about this armor.